“I have returned”: MacArthur’s Philippines Redemption

Eighty years ago, in one of the most iconic moments of World War II, General Douglas MacArthur declared, “I have returned” upon his triumphant landing on Leyte Island in the Philippines.

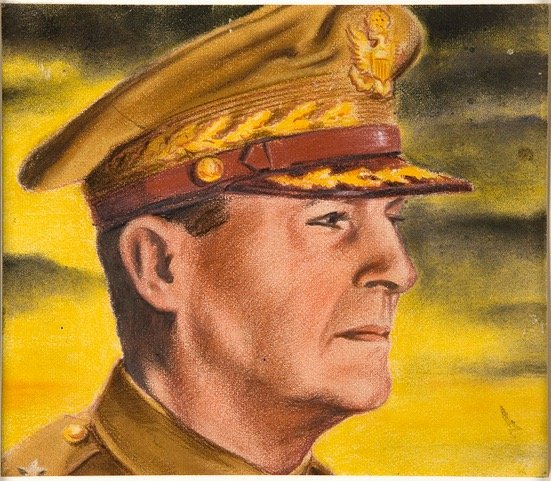

Douglas MacArthur, Leyte Island, Philippines, October 20, 1944

Paired with the iconic photographs captured as he waded ashore on October 20, 1944, this famous phrase marked the beginning of the U.S.-led liberation of the Philippines and the fulfillment of MacArthur’s “I shall return” promise made in 1942 when he was forced to flee to Australia after narrowly escaping Japanese forces that had surrounded his position.

The U.S. and Philippine Armies had suffered devastating losses in 1941-1942 when they were caught unprepared by a major Japanese Air Force attack in the immediate aftermath of Pearl Harbor on December 8, 1941. The first waves of Japanese aircraft destroyed nearly 50 percent of the American warplanes at Clark Field in Luzon. By February of 1942, with Japanese forces tightening their grip on the Philippines, MacArthur was ordered by President Roosevelt to relocate to Australia.

After months of fierce fighting in the Battle of Bataan (January-April 1942), American and Filipino forces were compelled to surrender to the Japanese. Many consider it to be the worst military defeat in U.S. history, with 23,000 American military personnel and roughly 100,000 Filipino soldiers killed or captured.

Despite his ignominious retreat, MacArthur – renowned for his military genius, courage and larger-than-life leadership style – emerged as a central focus of U.S. war propaganda and a revered symbol of Allied resistance to the Japanese. George C. Marshall, personally averse the spotlight, played a leading role in this effort when he decided that MacArthur would be awarded the Medal of Honor in 1942 “to offset any propaganda by the enemy directed at his leaving his command.”

Portrait of General MacArthur

MacArthur, who had deep, long-standing connections to the Philippines and its President, Manuel Quezon, was bound and determined to live up to his “I shall return” promise. With the tide of war turning in July of 1944, MacArthur succeeded in convincing President Roosevelt that the U.S. had a moral duty to liberate the Filipino people from the brutal Japanese occupation.

MacArthur was keenly aware of the power of his “I have returned” statement and the visuals captured on Leyte Island 80 years ago. The footage – which was broadcast globally – had an enormous impact, boosting the morale of both the Filipino people and the Allied forces.

The Allies’ subsequent victory in the Battle of Leyte Gulf (October 23-26), the largest naval engagement of World War II, helped ensure the fulfillment of Macarthur’s promise to destroy enemy control over the Philippines.

MacArthur’s panache – his determination, resilience and unbridled confidence – were an essential source of inspiration and motivation at this pivotal moment in history. The successful 1944-1945 Philippines campaign was both a personal vindication for MacArthur and a testament to his unique and larger-than-life leadership style.

Marshall and MacArthur: Polar Opposites with Mutual Respect

Born in the same year, George C. Marshall and Douglas MacArthur were towering historical figures whose careers spanned both World Wars and the early period of the Cold War. They were both strong, effective leaders with starkly different personalities and leadership styles.

“Marshall was as reserved as MacArthur was flamboyant, as self-effacing as MacArthur was egotistical. The two men offer a fascinating study in contrasts.” - PBS

As Army Chief of Staff, Marshall played a big-picture, strategic role during World War II, while MacArthur was a hands-on commander focused on operations in the Pacific. This dynamic often created tension and between the two strong-willed men, as MacArthur wanted more resources and autonomy for his theater, while Marshall had to balance global priorities. The Allies’ “Europe First” strategy irked MacArthur, who constantly complained to Marshall that their needs in the Pacific got “short shrift.”

Marshall’s reluctant support of President Truman’s decision to relieve MacArthur of duty in 1951 during the early stages of the Korean war marked a painful end of their often turbulent, yet mutually respectful relationship.

Another point of contrast: While Marshall was firmly apolitical, MacArthur pursued the presidency for years – both in and out of uniform.

“On balance, when one considers what each man accomplished during a long and often perilous stretch in history, one thing seems clear: America was lucky to have them both.” - PBS